Major General Donald Isles OBE

Lt-Col (later Major-General) Donald Isles commanded 1DWR between 1964 and 1967. After three years as a mechanised battalion in 12 Infantry Brigade, based in Quebec Barracks, where time was mostly spent on exercise in Germany, Norway and Denmark, the battalion was sent to Cyprus, as part of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force (UNFICYP) in April 1967. This is Maj Gen Isles’ first hand account of that six month tour.

Lt-Col (later Major-General) Donald Isles commanded 1DWR between 1964 and 1967. After three years as a mechanised battalion in 12 Infantry Brigade, based in Quebec Barracks, where time was mostly spent on exercise in Germany, Norway and Denmark, the battalion was sent to Cyprus, as part of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force (UNFICYP) in April 1967. This is Maj Gen Isles’ first hand account of that six month tour.

1967: 1DWR in Cyprus

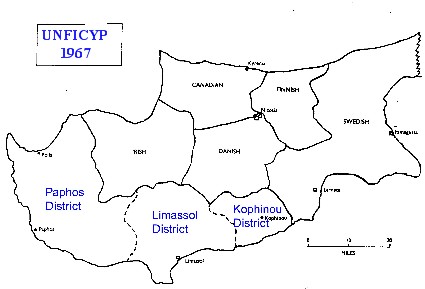

We were responsible for Limassol Zone, an area of some 1,500 square miles on the west and south of the Troodos Mountains. It extended from Pomos Point in the north to Larnaca in the east and included much of the most rugged country in Cyprus. Apart from the main roads (certainly no motorways in those days), which are mostly near the coast, movement between the villages was by means of narrow, stony tracks which twist and turn to match the contours of the mountain sides. Average speeds seldom exceeded 20mph and distances were large – from one extremity of the Zone to the other is some 140 miles. The sketch map below shows how the Zone was divided into Kophinou, Limassol and Paphos Districts.

My Battalion HQ, or HQ Limassol Zone, was in Polemedhia Camp in Limassol with the majority of HQ Company. This camp also housed the Limassol District HQ and two rifle platoons. There were also three rifle company headquarters each functioning as a District HQ with a fourth rifle company headquarters, within Paphos District, at Polis. The latter, with only one platoon, kept a close watch on the usually quiet northern flank of the Zone, but was under command of Paphos District. The Battalion, with 824 men, was organised into the Recce Platoon; twelve rifle platoons, each with a minimum strength of one officer and 24 men; two ad hoc reserve platoons formed from the administrative men of HQ Company, and reserve sections created at every HQ from any men who could be made available.

In support of the Zone was a 30 strong detachment of the United Nations’ Civil Police. At first these were New Zealanders who were then replaced by Australians. ‘A’ Squadron 5th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, in armored cars, was also located in the Zone but though available to me in an emergency it was the designated Force Reserve for the southern part of the island. Outside reinforcements, again at times of crisis, came from the Canadian Recce Squadron, the Danish, Finnish and Swedish battalions.

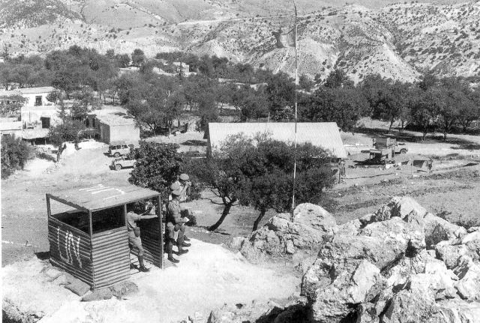

The above is the background to our time in Cyprus from May to November 1967. I had been on a recce in April and had found one disturbing fact. It was that Kophinou District was under command of the Swedish District Commander. As Kophinou was a distinct trouble spot I did not relish my soldiers being away from my control and I was determined to change it. It took about a month, but by June Kophinou was under my command and I had the battalion in a tidy state. Charles Huxtable (later General Sir Charles Huxtable CBE) commanded at Kophinou, Peter Hoppe at Limassol, at first Rodney Harms, my 2IC, at Paphos and then Jim Newton, while Robin Stevens was up in the north at Polis. For our six month tour I can safely say that, once a week, I saw every man in the battalion. Life for the soldiers manning an OP could be most tedious yet, once there happened to be trouble between Greek and Turk, there was very often much to be done. My section commanders did a most tremendous job in sorting out many petty, but potentially serious, problems between the two communities. Somehow the Yorkshire common sense and phlegm were quickly understood by both communities and the situation de-fused. If not handled properly, relatively minor issues could have affected the whole peace keeping operation in Cyprus.

There were four large-scale ‘shoot-ups’ involving the firing of nearly two thousand rounds of small arms and larger calibre rounds on each occasion. Shooting incidents of a few rounds were commonplace, as were minor clashes between Turkish Cypriot fighters and Cypriot Police or the Greek National Guard, entailing the hurling of stones and the shouting of threats and insults.

Bomb incidents and vendetta killings were endemic to Cyprus and there is no doubt that the political situation was blamed for some occurrences, which had more of a personal than a political motive behind them.

During such incidents it was essential to establish a UN presence as quickly as possible before it had a chance to escalate. For one of the more serious incidents at Kophinou/Ayios Theodhorous, all of nine platoons and all the armoured cars of the squadron were required for interposition between Greeks and Turks. At Kophinou I had Charles Huxtable, with five platoons and two troops of armoured cars permanently under his command, based in the former police compound.; Mehmet, a regular Turkish officer from the mainland, was the Turkish Fighters’ leader. He was young and most aggressive, not only to the Greek Cypriots, but also to the United Nations. The Black Watch, before us, had had an incursion into the compound when some forty fighters rammed the wire with a truck and, once in, proceeded to batter the Jocks with pick handles and also caused considerable damage to UN property.

The crux of the problem at Kophinou was that a road off the main Nicosia-Limassol road ran to the village of Ayios Theodhorous. Additionally there was a Cypriot Police post at Skarinou adjacent to Kophinou. Ayios Theodhorous was a mixed Greek/Turkish village and thus the Cypriot Police felt compelled, and indeed had the legal right, to visit it by a jeep patrol at least daily. The Turks had never liked this and on the 20th of July, to express their disapproval, they opened fire on some Greeks in the village. The Greeks retaliated and the firing went on throughout the night. Charles and I had made our way to Ayios Theodhorous and spent the whole night in Martin Bray’s platoon position right in the middle of the crossfire. About dawn we managed to arrange a ceasefire but, as I have said above, nine platoons and the armoured squadron were needed to keep the warring parties apart. It was not a pleasant experience but, as in Limassol, no one was hurt and this despite the use of heavy machine guns from the surrounding positions in the hills.

However, I knew that Kophinou would eventually cause grave problems for the United Nations unless we could get rid of the Turkish defences which were well dug-in around Kophinou and Ayios Theodorous. Along with Charles I drew up a plan for a ‘peaceful’ battalion attack on the Turkish positions. The idea was to saturate the area with Blue Berets and advance up to and through the Turkish defences, relying, we believed, in that the Turks in the face of such numbers would not open fire. Needless to say the plan was not approved but, if it had been, it would certainly have prevented the disaster which overtook the 1st Green Jackets on the 16th of November, barely a week or so after they had taken over from us. On this occasion, the Greek National Guard in considerable numbers and with artillery and heavy weapons assaulted Kophinou killing 22 Turks and wounding nine. General Grivas himself was involved in this outrage. It was clear that the Greeks had waited until the experienced Dukes had left and the new Green Jackets had taken over before putting in their attack. Perhaps one good outcome of this outrage was that General Grivas went back to Greece and was never seen again in Cyprus. He had caused so much trouble in his time and as a UN soldier, I resented having to salute him when, on occasions, he drove through our Zone in his black Mercedes staff car flying his Greek commander’s flag.

In the first week in November Frank Kitson (later General Sir Frank Kitson) and his Green Jackets took over from us and we found ourselves back in Osnabruck with our families. We left two soldiers in hospital in Cyprus but they soon re-joined us. It had been a valuable tour and I enjoyed working with Mike Harbottle, the UNFICYP Chief of Staff and his staff officers.