Pte Clifford Garlick – WW2

Clifford Garlick was born on the 25th of May 1923 in Holmfirth His father worked as a road mender for the council. Clifford left school at 14 and his sister found him a job, at first yarn spinning, then scouring, in the local mill. It was a hard 48 hour week; and there was always someone waiting for your job at the mill gates. Money was tight in the Garlick family, Clifford’s father had been gassed in the First World War, whilst serving with the Royal Engineers.

Clifford Garlick was born on the 25th of May 1923 in Holmfirth His father worked as a road mender for the council. Clifford left school at 14 and his sister found him a job, at first yarn spinning, then scouring, in the local mill. It was a hard 48 hour week; and there was always someone waiting for your job at the mill gates. Money was tight in the Garlick family, Clifford’s father had been gassed in the First World War, whilst serving with the Royal Engineers.

Clifford was 19 when he was called up into the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. He completed his training at Brancepeth in County Durham. Prior to his call up he had never been out of the relatively small village of Holmfirth. From Scotland, he recalls he was sent to Bristol and from there posted to North Africa. The troopship took an evasive route through the Irish Sea to dodge German submarines, taking 10 days to reach Algiers. Clifford suffered with seasickness throughout and on arrival, the Germans attacked them and blew a propeller off the ship.

The Regimental War Diary indicates that the Battalion left Crieff, Scotland, by two trains, at 21:15hrs and 22:15hrs on the 25th of February 1943, to Avonmouth, by 15:00hrs the next day they were fully embarked on HMT Moreton Bay in Avonmouth Dock, with a Battalion strength of 40 Officers, nine Warrant Officers and 885 Other Ranks. They left Avonmouth on the 27th going up the coast to the Clyde and joined up with another convoy.

They arrived at Algiers port around 17:00hrs on the 9th of March. At 19:00 hrs, whilst mooring there was an air raid and the tugboat captain cast off his lines and headed out towards the open sea, away from the crowded and fully stocked ship, for safety. The ship drifted into the side of the harbour wall and damaged the propellor. The following day all the stores, equipment and men were transferred to the HMT Empire Pride, and at exactly 19:30hrs they set off again along the Algerian coast to Bone, now known as ‘Annaba’, arriving there at 17:00hrs the next day, again during an air raid. (Richard – Archives)

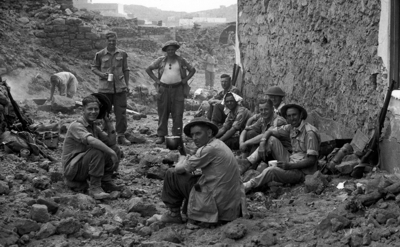

Whilst they were at Bone, preparing to attack the German forces, the monsoons started. The Battalion was camped four to five miles along the coast in tents. The weather had turned wet and there was heavy rain for several days. The ground turned into a thick quagmire of mud, resembling the battlefields of WW1. This resulted in some roads being washed away and a few landslides onto the roads, making walking and driving difficult. Elsewhere, even tracked vehicles and aircraft were getting bogged down; trying to dig them out was almost impossible. The Battalion was instructed to move, by road, on the 13th, to Gafour, In Tunisia. Audio archives from the Imperial War Museum record an artillery officer in the convoy saying they travelled on an irregular road with steep inclines and through a forest of Cork Trees. They arived in Garfour at 03:00hrs, just a few miles to the southwest of Bou Arada. On the 15th The Dukes moved into the line and started sending out patrols. A number of actions occured over the next few days as the battalion moved forward. (Richard – Archives)

They made their way forward, unaware Germans were watching them from camouflaged observation posts. It took about 5 days pushing through to reach the last hill only to find the enemy were at the top, lobbing hand grenades down on them, when suddenly there were six German tanks behind them, cutting them off from the rest of the Regiment. They were told to fix bayonets, and they ran down to the bottom of the hill, where the Germans’ tanks had them covered, and called on them to surrender. The German tank commander spoke perfect English, but nobody moved and so the German gunners opened up on them with machine guns. Several soldiers were hit, including the lad next to Clifford. He stayed with his badly wounded comrade, who was bleeding from leg wounds, helping to put him in a German motorbike’s sidecar.

Regimental War Diaries record that at around 22:30hrs on the night of the 20th of April the Right flank of the Battalion lines, at Banana Ridge, was infiltrated by German troops. ‘C’ Coy sent men to reinforce A Coy, and during this night two officers, Lt’s Naylor, Wraight, and about 30 men were reported missing. At 05:00hrs German tanks and Infantry came round the south of Gren Hill and attacked the Battalion. (Richard – Archives)

Clifford had not had any food or drink for several days and accepted his capture. He clambered up on a tank and one German soldier gave him a drink of cold coffee from his bottle, then the 50 to 60 prisoners were lined up and marched about 100 km to a farm where, exhausted, they slept for several hours. The next day they lined up to get a cold drink from a water tap and were given broad beans to eat in their mess tins, along with German black bread.

The prisoners were then marched to a POW camp, which was under the command of the Italians, where they spent the next two to three weeks. The Italians treated the British captives reasonably well. The sanitary arrangements were somewhat primitive; they had to dig holes for latrines, with planks across, and they also built a box to go over the top. The Italian guards couldn’t understand the box with holes in the top!

Approximately 500 Allied prisoners were sent to Tunis and put on a POW ship as the Germans were evacuating. The RAF was under orders to stop the Germans fleeing Tunis and they bombed the ship, after it had got a couple of miles out to sea. The Italian sailors decided to run the ship on to a sandbank, where they abandoned the ship, got into the lifeboats and left the prisoners behind. A German gun crew on the ship insisted one lifeboat should be left for their use and, after one of the gun’s crew was killed, they also abandoned the ship. The POWs quickly dipped the ship’s guns, in surrender, and draped white sheets over the decks to try and stop the attack, but the RAF continued bombing the ship. Two of the strongest swimmers decided to set off for the shore to try and stop the onslaught. Then one bomb went through one side of the ship and lodged into the other side, the heat setting fire to the bedding there. The surviving prisoners were rescued when the harbourmaster came out with boats from Tunis to take them off.

Clifford had also been injured. He had one shrapnel wound at the back of his neck and another in his arm, which had cut through his battledress. At Tunis a stretcher-bearer bandaged his wounds and he managed to get something to drink, everyone had dysentery Clifford drank some wine as he couldn’t find any water. He was sent to the hospital tent and there he found his mate who’d been shot in the leg during the previous battle. His German captors had given him first class medical treatment and this had saved him from losing his leg.

Clifford was patched up and went on to take part in the landing at Pantelleria. He watched the island being bombed, by both the Navy and the RAF. He went ashore on a landing craft and ran up the beach with a PIAT (Projector Infantry Anti-Tank) gun, which he considered no use at all, in those circumstances. As a result of the intensive bombing the landing was unopposed and Clifford was only there for two to three days. They found a water well, in a church and saw the Italian women and children re-emerging from where they had taken shelter.

The Regiment was brought back to Tunisia, to re-equip, before taking part in the landing at Anzio, where Clifford was one of the first to get off his landing craft. It was a straight-forward landing, but he soon found the Germans to be the better fighters and the allied soldiers were outclassed. ‘Anzio Annie’ fired every night, they didn’t get many supplies and sometimes survived for days on end just on army biscuits, which they usually crumbled to make a porridge.

“Anzio Annie” was actually two railway guns, making up the German K-5 RR battery that shelled the Anzio Beachhead. “Robert” and “Leopold” were the names the Germans gave the two guns. When the Allies broke out of the Anzio Beachhead, the German moved the guns to Civitavecchia, just north of Rome. There “Robert” and “Leopold” were spiked with explosives and immobilised to prevent them from falling into Allied hands. On the 7th of June, 1944, the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th Division ‘captured’ the guns. Leopold was the least damaged of the two and it was moved to Naples, then embarked aboard the liberty ship Robert R. Livingston and shipped to the Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) in Maryland, USA. (Richard – archives).

“Anzio Annie” was actually two railway guns, making up the German K-5 RR battery that shelled the Anzio Beachhead. “Robert” and “Leopold” were the names the Germans gave the two guns. When the Allies broke out of the Anzio Beachhead, the German moved the guns to Civitavecchia, just north of Rome. There “Robert” and “Leopold” were spiked with explosives and immobilised to prevent them from falling into Allied hands. On the 7th of June, 1944, the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th Division ‘captured’ the guns. Leopold was the least damaged of the two and it was moved to Naples, then embarked aboard the liberty ship Robert R. Livingston and shipped to the Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG) in Maryland, USA. (Richard – archives).

They had to quickly organise attacks to try and push the Germans back. The trenches were full of water and they were soaked wet through for weeks on end. There was no rest at all, as they spent two hours on duty and two hours off, sleeping wherever they could find a place to lay down. On one occasion they advanced up a railway embankment where they heard Germans talking on the other side, then suddenly German tanks came round both sides of the embankment behind Clifford and his mates, so he and his comrades started to pull back, sheltering in craters. They eventually managed to get back safely, but they had no weapons or ammunition, they rejoined the other Dukes further back. They were told to go back to the front by a Sergeant; but Clifford refused as they had no weapons, that probably saved his life, as only half a dozen men survived the attack.

Clifford lost a good friend at the railway embankment, Attwell, where Clifford dug him a grave. Another of his mates was hit by a sniper, he screamed all day, although he was close they were pinned down by a sniper so they couldn’t rescue him. At Anzio Clifford was in a trench with Eric Mallinson when three reinforcements arrived with a Corporal, all of them not knowing what to do. Clifford advised them to quickly dig a trench. Later, whilst they were asleep shells started coming over and one hit a box of ammunition, the resulting explosion burying them in their trench. Stretcher-bearers pulled them out and it took Clifford a long time to recover from the shell-shock.

After Anzio, Clifford was sent to work in the cookhouse. The ‘Dukes’ were advancing into Rome and he recalled being in an attack on his 21st birthday, rigged out with fluorescent flares. He could see other soldiers being injured when the flares were hit by gunfire, one lad had just gone 19 and he died talking about his girlfriend and his mother.

Later Clifford put in for transfer to the Army Catering Corps. He had made breakfasts for 100 men before being sent back to England, where he spent 6 weeks in Aldershot doing nothing but sweeping up. He didn’t like it, so he put in for another transfer back to cooking at Yeovil.

Clifford was finally demobbed just before Christmas in 1947, and returned to work in the mill “though you had to beg for your job back” he recalled. Clifford worked in the same mill until his retirement. Clifford met Phyllis whom he married in 1948 and they completed their family with four children, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Clifford was sorry to leave the Dukes, even for a safe job. Clifford doesn’t think his experiences affected him badly, despite seeing so many killed, but he said “I’ve seen too much”. He illustrates this with a recollection of a young man he served with in North Africa, “a right grand little lad, who used to sing ‘Bless this House’. Shell-shocked, this lad got up and ran towards the German lines and his own corporal shot him. It gets to you, bomb happy people didn’t last so long, they more or less gave in.” Clifford says he’s had no bad dreams, but acknowledges that people don’t realise what War Veterans have been through, it’s something he feels he has to accept.

This is a record of Clifford Garlick’s Service with the Duke of Wellingtons Regiment during World War 2, from 1942 until 1947.

Interviewed by Tracy Craggs, Regimental Archives Section, Audio Archivist.