Pte Ron Boothroyd – WW2

Gunner R E Boothroyd, A Coy 4th Battalion The Duke of Wellington’s Regiment

From his memoir, ‘My Life as a Soldier’.

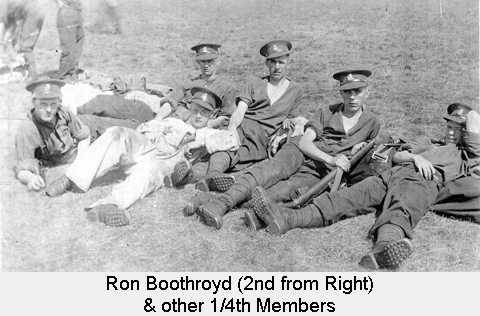

Ron Boothroyd joined the Territorial Army in May 1932.

I joined the 4th Infantry Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regt. I went to the Drill Hall at Halifax where they gave me all my kit and told me to report to ‘A Coy’ at Sowerby Bridge.

I joined the 4th Infantry Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regt. I went to the Drill Hall at Halifax where they gave me all my kit and told me to report to ‘A Coy’ at Sowerby Bridge.

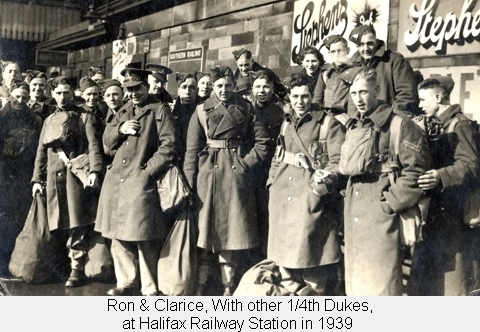

In late summer 1939, Ron was asked to report for duty at the Drill Hall in Halifax where the Company converted from Infantry to 229 Battery 58th Anti-Tank Regiment Royal Artillery (1/4th DWR). The next morning Britain declared war on Germany. Ron’s Company spent a few weeks training in Halifax, then travelled by train to Knaresborough where they were given 2 Pounder Anti-Tank guns and trucks and new battle dress.The training became tougher and more dangerous as live shells were used. After some months they left for Sheffield.

Now we travelled by road in our own trucks towing our guns. I was a limber gunner, when travelling I sat on the gun. Wherever that gun went, I went with it.

They soon left Sheffield for Shepshed in Leicestershire and then made their way to Dover. The barracks were well hidden in the White Cliffs and they boarded the SS Autocarrier bound for Calais in France during the night.

The Troopships sailed from Dover with the SS Autocarrier carrying the 229th Anti-Tank Battery at 10.40 am. This Battery left Sheffield, where it was stationed at 4.45 am on the 21st May and did not reach Dover till 1.10 pm next day. They had been expected to sail at 10.30 am but the SS Autocarrier had six wireless trucks on board destined for another unit. In consequence there was no room for the whole of the Battery. Their commander, Captain Woodley, was ordered to embark only two of his Troops and his battery staff. The remaining men were to follow ‘within twelve hours’. Only eight of their twelve guns were loaded on the ship. The rest never arrived at Calais.’ (Taken from The Flames of Calais, by Airey Neave, p93.)

We landed in France with the BEF. As we sailed into the harbour we could see ships masts and funnels sticking up out of the water, the Germans had bombed them.

Ron’s Army mates were Joe Ackroyd and Tommy Deadman, and as the three men’s surnames were first in the alphabet, they led the charge off the ship under sniper fire from Fifth Columnists, Joe with a rifle and bayonet, Tommy with a bag of grenades and Ron with his Bren Gun.

Ron’s Army mates were Joe Ackroyd and Tommy Deadman, and as the three men’s surnames were first in the alphabet, they led the charge off the ship under sniper fire from Fifth Columnists, Joe with a rifle and bayonet, Tommy with a bag of grenades and Ron with his Bren Gun.

Joe kicked the house and shop doors in, then Tommy threw a grenade in, then I sprayed it with my Bren Gun. When we had cleared the dock area, they unloaded the trucks and guns. When everything was ready every gun team mounted their trucks and guns and went flying through the town of Calais as fast as possible, under rifle fire. Every gun went to a different spot outside the town in the country about one mile apart.

We built our gun pit by the side of a country lane between two small hills and a deep pond in front of us so that Jerry tanks could not flatten us.

They spent two nights at the gun pit. One of their men, a Militiaman, became hysterical and ran away, they never saw him again. The next morning their Officer, Lt Bennett, brought them food and news – the enemy had broken through and the British Infantry had retreated back to Calais. They were ordered to destroy their gun and return to the docks.

We climbed aboard the truck and made like lightening for Calais and went flying through the town until we came to the dock area – all the docks had been sealed off by wrecked cars, trucks and big guns, so we wrecked our truck and rammed it in amongst the others. We found about twenty men and two officers of our mob so joined them.

We dug a trench on top of a long ridge and kept the Jerries out of the docks because a boat was taking wounded off to a hospital ship out in the Channel. They started shelling us with trench mortars and rifle… We stayed there all that day shooting into the town, the Jerries could not shift us.

During the night they were persistently attacked by German aircraft and when daylight came they tried to make their way to a coastal fort where more British troops were shooting at the town.

We had to run and crawl through the sand hills, at one point we had to cross a gap about 20 yards wide, which was under fire from Jerry snipers. We had to dash across in ones and twos. Two of our gunners got killed crossing, Joe and I stopped to get their dog tags, the bullets flying all around us but we didn’t get hit.

We had to run and crawl through the sand hills, at one point we had to cross a gap about 20 yards wide, which was under fire from Jerry snipers. We had to dash across in ones and twos. Two of our gunners got killed crossing, Joe and I stopped to get their dog tags, the bullets flying all around us but we didn’t get hit.

Ron and his comrades helped to defend the fort until they ran out of ammunition. They could see large Royal Navy ships about three miles off the coast and they signalled for help. (At 2pm on the 25th May, Nicholson received this message from Eden: “Secretary of State to Brigadier Nicholson: Defence of Calais to the utmost is of highest importance to our country as symbolising our continued co-operation with France. The eyes of the empire are upon the defence of Calais and HM Government are confident you and your gallant regiments will perform an exploit worthy of the British name.” This message was passed around the Regiments involved in the defence of Calais.)

They answered, “Sorry, we cannot land. Carry on, the eyes of the Empire are on you. Good luck!” And then they started shelling the town. They frightened both us, and the Jerries, out of our wits. The shells sounded like express trains flying through the air and when they landed there was half a street missing… Anyway we had run out of ammo so the Jerries came into the fort. We threw all our firearms into the sea and just kept our pay books… I now became a Prisoner of War.

They marched us away that day and all along the roadside were dead and wounded British soldiers. The wounded were begging for water but the Jerries would not let us stop, they said their stretcher bearers would collect them.

The prisoners were marched through Calais and out into the countryside, it was very hot and dusty. Their only food was given by French women – buckets of water and pieces of bread to share, but hundreds of prisoners had joined the march so there was little to go round. They walked through France and Belgium and into Holland.

When we arrived at the Dutch border at Maastrict all the Dutch people came out and filled long tables with food, bread, sausage, cheese and milk – the best sight we had ever seen. The Jerries let us have a good meal and a wash in a stream. To thank the Dutch the best way we could we gave them three cheers, tidied ourselves up, fell in properly and marched away as smart as ever. The Dutch people cheered, the women cried. The Jerries went crackers shouting and firing their rifles into the air.

![]() Once in Germany, they were loaded into cattle trucks and travelled for days through Germany and Poland to Gliewitze in Upper Silesia. Their camp, Lamsdorf Stalag VIII B, was about five miles from the station.

Once in Germany, they were loaded into cattle trucks and travelled for days through Germany and Poland to Gliewitze in Upper Silesia. Their camp, Lamsdorf Stalag VIII B, was about five miles from the station.

They packed us into long huts three wooden bunks high, one blanket and a lousy, straw mattress. Polish prisoners had been there before us… At breakfast time we got a cup full of acorn coffee, 4oz of black bread and a spoonful of margarine and jam. At dinnertime, a bowl of watery soup (cabbage) and two or three spuds in their jackets, if you got a bad one it was hard lines. Tea time, a cup of mint tea. That was our daily food for the next few months.

Ron, Joe and Tommy volunteered to labour in the local community helping to build a dyke. They were given more food, clean beds and enjoyed the company of the villagers.

After a few weeks I was taken ill so a guard took me back to Stalag VIII B, I did not see my mates anymore until after the war. A doctor examined me and sent me to hospital. They took me in an ambulance with a mad Polish prisoner who was in a straight jacket and gagged and a big bull mastiff whose breath stank. The guard sat in the front, safe. We arrived at hospital, then they examined me and put me to sleep and operated on my neck.

He spent two weeks recovering in hospital and after a night with French POW’s at another camp, he was sent back to Lamsdorf. After a few weeks, he felt restless and volunteered for another working party. This time the work was in a coal mine.; Ron was working on a coal-face about five feet high and twenty feet long with four Polish prisoners and a German Stiger Boss.

We had big, hull shaped shovels which weighed a ton when full and I was fairly weak with the lack of food and hospital so I only half filled my shovel. The Boss went barmy, screaming and slavering and then he picked his long drill up so I threatened him with my shovel – it was shiny and as sharp as a razor. I shouted, ‘I am an English soldier, not a Polish slave!’ He left me alone after that so I sat down holding my shovel and did not do another stroke. They only filled 20 tubs that shift.

The next morning a guard came to take Ron from the coal mine, he assumed he was going to prison, but was taken to another coal mine in Megtal. The work was very hard and dangerous but this time there were more British labourers and Ron became good friends with Syd Yates, who slept in the bunk below his. They hated mining and when a Polish worker told them that they would only be allowed to leave the pit if they developed eye problems, they decided to feign this. They were examined by two doctors, and deliberately failed all their tests. Syd and Ron were taken to a small camp near Silesia – there were 30 prisoners and a Sergeant. There were six guards and a German officer.

The officer was very fair. He went on leave one day and when he came back the guards told us that he had lost his wife and children by British bombing. He did not blame us at all. He had us all in his office and asked us what sort of work we could do. I said that I was a tailor and I could do first aid. (I could neither thread a needle or roll a bandage) but I got the job and never went to work again. I soon learned to sew patches on trousers and darn socks. I managed to get a book on first aid so I managed that except for one or two accidents. One prisoner called Burton was killed by a train on a job site. The Jerries gave him a proper military funeral in a proper graveyard, a coffin, a Union Jack, a wreath and they fired eight shots over him.

Red Cross Parcels and provisions from local traders supplemented the prisoners’ diet. They ate reasonably well, especially when Ron prepared ‘Poison Stalag Pie’ which consisted of a mess tin of meat (usually corned beef) and two inches of mashed potato. A surplus of prunes and dried fruit were used for a distilling project – potatoes, bread, and corn were added and after a month it was boiled and tested. The potion seemed to be pure alcohol so it was diluted until it could be drunk.

Some of the Scots said they were used to drinking whisky and drank theirs neat which was a bad mistake. Two of them went barmy and started fighting and screaming and wrecking the place. The guards came in and we had to help them to tie them up. Then another went blind. The day after they were sent back to Stalag VIIIB. After that the making of spirits was banned.

The parcels and mail did not always bring good news. Syd lost the girl he was engaged to, she had married a soldier from the USA. He was sickened for a while. Getting letters like this made us talk about escaping and trying to get home.

The prisoners divided into pairs and began to plan to escape. They made their own plans and kept them quiet. The first pair took advantage of a sports day out of the compound.

Someone suggested racing, so two lads walked about two hundred yards away and put two small bundles on the ground and came back and told the German officer they were going to run there and back to see who won. The Jerry fired his revolver to start them off. When they reached the bundles they snatched them up and kept on running. We all cheered. The Jerries fired their rifles but missed. They vanished over the horizon.

In August 1944, it was Ron and Syd’s turn to escape. They plaited a rope out of plastic parcel wrap, made a hole in the roof of the shed and climbed through. They did not get far, the guards borrowed hunting hounds and searched the forest. Ron and Syd were caught by four policemen, handcuffed and handed back to the guards. They were locked in two narrow clothes lockers for 12 hours with no food or water.

In August 1944, it was Ron and Syd’s turn to escape. They plaited a rope out of plastic parcel wrap, made a hole in the roof of the shed and climbed through. They did not get far, the guards borrowed hunting hounds and searched the forest. Ron and Syd were caught by four policemen, handcuffed and handed back to the guards. They were locked in two narrow clothes lockers for 12 hours with no food or water.

When they let us out, all was forgiven on both sides.

The winter of 1944 brought frost and snow blizzards. A few days after Christmas Ron and a guard went to collect Red Cross parcels from a barracks store about five miles away and brought them back on a sledge. They could hear gunfire in the distance and returned to the camp where all the prisoners were informed of the Russian advance and to pack up to move out. They filled their kit bags with food and clothes and started trudging through the snow all through the night and the following day. The next night they stayed in a farmhouse, the farmer boiled enough water for the guards and prisoners to enjoy a hot drink but the next morning they continued to march.

Every day was a repeat except some farms were abandoned, so no hot water. But Syd and I picked twigs up on the way, plenty in these forests, and so we had a fire to cook on. We knocked off an odd chicken now and then. We left Silesia and went into Poland and things now began to get very hard. We had now joined a long queue of POWs (‘the long march back’). The Jerries gave us what food they could get each day. Then some lads got frostbite, one of our lads lost his toes and they put him on a cart and we did not see him again. Then we started passing bodies on the roadside some had just laid down and died, most had been shot. Our party still stuck together with our own guards but we had to be careful. There were young barmy Nazis walking up and down and shooting at anything.

At an empty farm, Ron found two oxen and they were taken to pull a cart carrying all the kit. The march continued through Poland and into Czechoslovakia and Ron led with his oxen ploughing a sort of path through the snow drifts. Soon, the animals became exhausted and were traded for food at a farm.

Danger increased as American and Russian planes strafed the German transport columns travelling with the prisoners, so Syd, Ron and two more lads decided to try and make their own way home and headed for Bavaria, dodging retreating German troops. Ron had taken a revolver from a dead German Officer, and he was elected group leader. Tired and hungry they reached a large village and slept in the school house. The next morning they agreed they had marched far enough, that they would stay at the village until whichever Allies arrived and when the Mayor and his councillors approached the next morning, they asked them for proper billets, in return they would look after them when the troops arrived. Syd and Ron went to stay with the Mayor and had a bedroom each, good food, a shave and haircut and freshly laundered and pressed uniforms.

One night at about midnight, the Mayor came to our rooms. He said that there were French ex POWs coming through the town breaking into the houses and stealing, and raping the women. Anyway, they came to our door, I opened it, they saw us in British uniforms. There were five of them and they started shouting and trying to push in so I shot their leader in his arm and they ran like hell. No more bother with them.

The Mayor was very grateful and gave Ron a ladies wristwatch and a ring. Two weeks later they heard more gunfire and the Mayor asked them for help again. The villagers had heard that the Americans were coming and that they would rape the women and eat the children. Ron suggested it was German propaganda but they were still fearful.

One day, a 6ft tall Jerry officer came down the lane with his hands up, his chest full of medals, a dagger and a revolver on his belt. He said he wanted to surrender to the British. He said he was a Dane and he was not fighting Russian Communists. Anyway, I took his revolver and dagger off him but let him keep his medals, locked him in the garden shed and gave him some food and drink. He was a clever one and said he wanted proper lodgings like us. The next day the Yanks came. Me and my mates stood near the entrance of the village to wait for them, we did not know what to expect, all the people stayed in the schoolroom frightened to death. Anyway, in came the Yanks on each side of the lane, they were covered in twigs, grass and feathers and when they saw us they stopped dead, they dare not move. One of their officers came up and we told them we had taken the village so we handed it over to him. He dismissed his troop and within five minutes they were playing pokey dice with the kids and giving them chewing gum.

One day, a 6ft tall Jerry officer came down the lane with his hands up, his chest full of medals, a dagger and a revolver on his belt. He said he wanted to surrender to the British. He said he was a Dane and he was not fighting Russian Communists. Anyway, I took his revolver and dagger off him but let him keep his medals, locked him in the garden shed and gave him some food and drink. He was a clever one and said he wanted proper lodgings like us. The next day the Yanks came. Me and my mates stood near the entrance of the village to wait for them, we did not know what to expect, all the people stayed in the schoolroom frightened to death. Anyway, in came the Yanks on each side of the lane, they were covered in twigs, grass and feathers and when they saw us they stopped dead, they dare not move. One of their officers came up and we told them we had taken the village so we handed it over to him. He dismissed his troop and within five minutes they were playing pokey dice with the kids and giving them chewing gum.

The officer had three sergeants and some German prisoners so they made a wire compound and used the school as an office. We decided to hand our clever German prisoner over to the Yanks, but warned him not to be so clever and to put his medals in his pocket. He said, “Heil Hitler.” We gave him to the Yankee MP who ripped his medals off, stamped on his feet, butted him in the face – he had a steel helmet on, and flung him and his medals into the compound.

The four British soldiers decided to leave. Ron took a motorbike and drove around the countryside to see what was happening and realised they could get caught up in the German retreat. They repaired an old Opel car, painted a large, white star on the front and the Americans filled the petrol tank and gave them some K rations.

The day after they had left the village, they came under rifle fire. They continued on an off road route, keeping as low as possible, and got through the German lines.

Then the Yankee tanks started firing at us. We threw our (German) helmets away and stood up waving but they got us. The car set on fire, nobody hurt we jumped out with our hands up. The Yanks made a fuss of us, gave us food, fags and beer then turned their backs and let us knock a jeep off then off we went for Belgium.

They travelled about twenty miles until they reached a US Airforce camp. They had a meal there and noticed many planes landing and taking off again. Ron asked where the planes were going and he was told the pilots did not know until they were in the air but the destination would be England, France or Russia.

I asked one pilot if he would take us four and he said “yes, if you want to risk it. There are no parachutes for you if we get shot down.” We flew around for about an hour then started to land, I thought England, but it was only Rheims in France.

They landed, had a meal in a Red Cross hut and waited for five Halifax bombers to land, hoping for a lift home.

The planes were there but a Yankee Red Cap said we could not go because we had not been processed. We didn’t know what he was on about and the Canadian crew booed him, so out came (my) revolver and I told him to p— off and We got on the first plane, the Canadians cheered and set off. I was laid in the bomb bay looking down through the glass bottom. I saw France, then the English Channel then the White Cliffs of Dover. After all these years we were back in England in one hour.

The pilot had radioed through that he was carrying four ex POWs and a truck was waiting for them at the airfield. They were taken to a transit camp where they were showered, deloused, given haircuts and new uniforms. They were only allowed to keep personal possessions, all their old kit, the revolver and the dagger were taken.

They gave us each an Air Force girl to show us around. They took us into the YMCA for a slap up meal and a couple of pints and fifty fags. Then they handed us over to an Army sergeant to take us back to the Army. The girls said goodbye, mine gave me a kiss. They took us to a large transit camp, gave us all five pounds and 24 hours off duty, after a couple of days they gave me a travel warrant to go home on leave until further notice.

Clarice was still in the ATS at Huddersfield so I went there to meet her. They let her out for 24 hours so we went to a pub, booked a room and stayed all night. Eventually we both got de-mobbed and settled down to married life.

This condensed version of Ron Boothroyd’s wartime experiences is reproduced with the kind Permission of David Cochrane, DWR Archives Dept, who conducted the research, and Ron Boothroyd’s family.

©Photo’s by Ron Boothroyd